Narrative

Six of the world’s seven species of marine turtle (green, hawksbill, loggerhead, flatback, leatherback and olive ridley turtles) feed, nest and/or migrate through Torres Strait.

Marine turtles are an important feature of the natural and cultural landscape, and the region provides important refugial habitat for certain stocks. The region contains one of the largest remaining nesting populations of hawskbill turtles globally, and various cays on the fringe of the Torres Strait comprise the largest remaining rookery in the world for green turtles.

Marine turtles play an important ecological role in the region, contributing to food webs and nutrient cycling in seagrass meadows and coral reef ecosystems. Turtles feature prominently within

the knowledge systems, customary laws and livelihoods of local traditional communities, and play a significant role in the region’s traditional subsistence economy. Leatherback and olive ridley turtles are the least abundant and are not known to nest within the region.

Turtle populations are especially vulnerable to threats because individuals take decades to reach maturity, there is high natural mortality of young, they have strong loyalty to nesting and foraging areas, and migrate over long distances to breed. They use beaches and marine environments to complete

their lifecycle, which makes them particularly vulnerable to predation, hunting, egg harvest and bycatch. Marine turtles also have characteristics that contribute to population resilience, including each population being supported by multiple breeding locations and widely dispersed foraging populations.

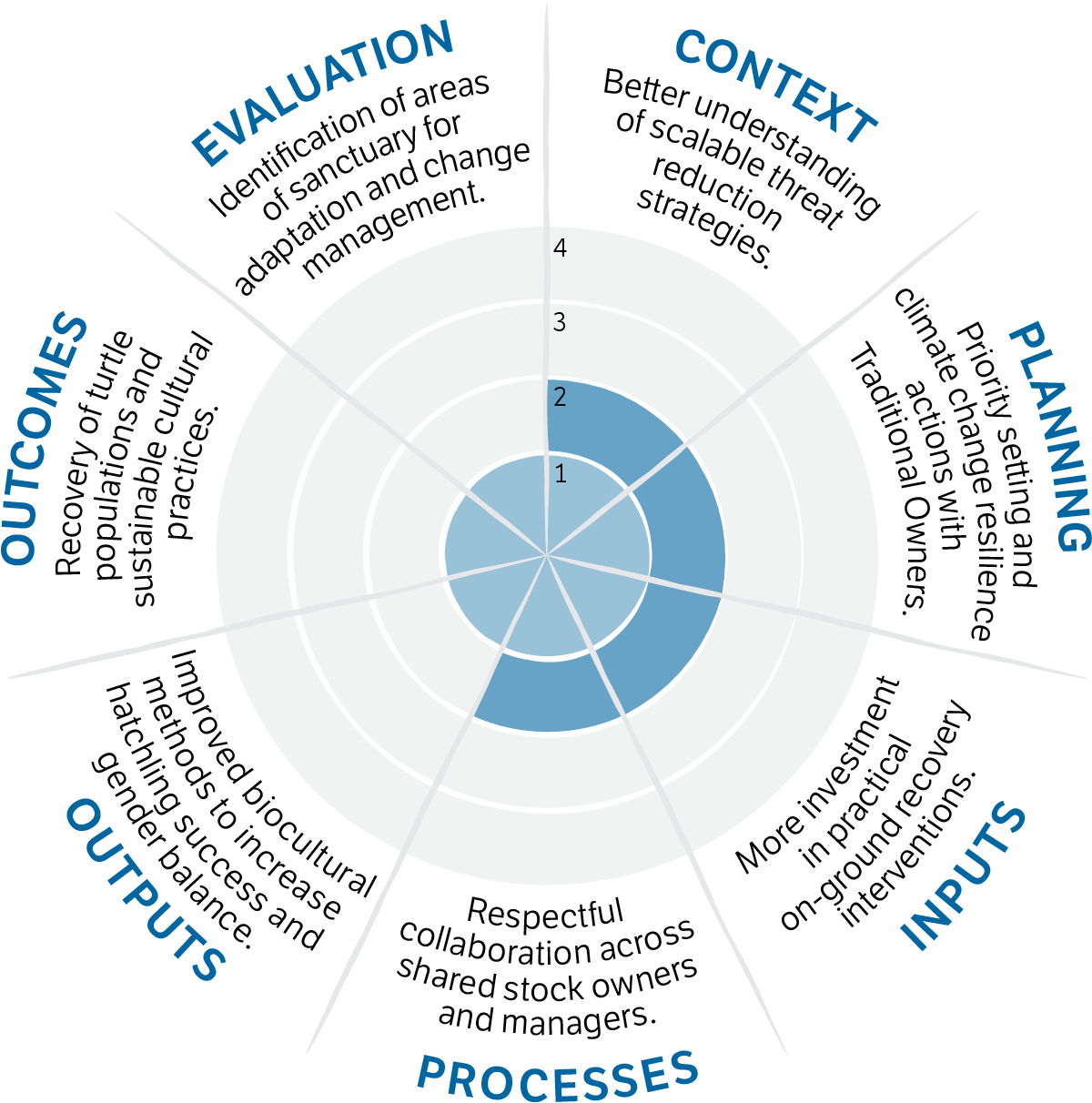

Community-based turtle and dugong management plans remain the cornerstone of local marine turtle protection and management efforts by Traditional Owners.

What is already happening?

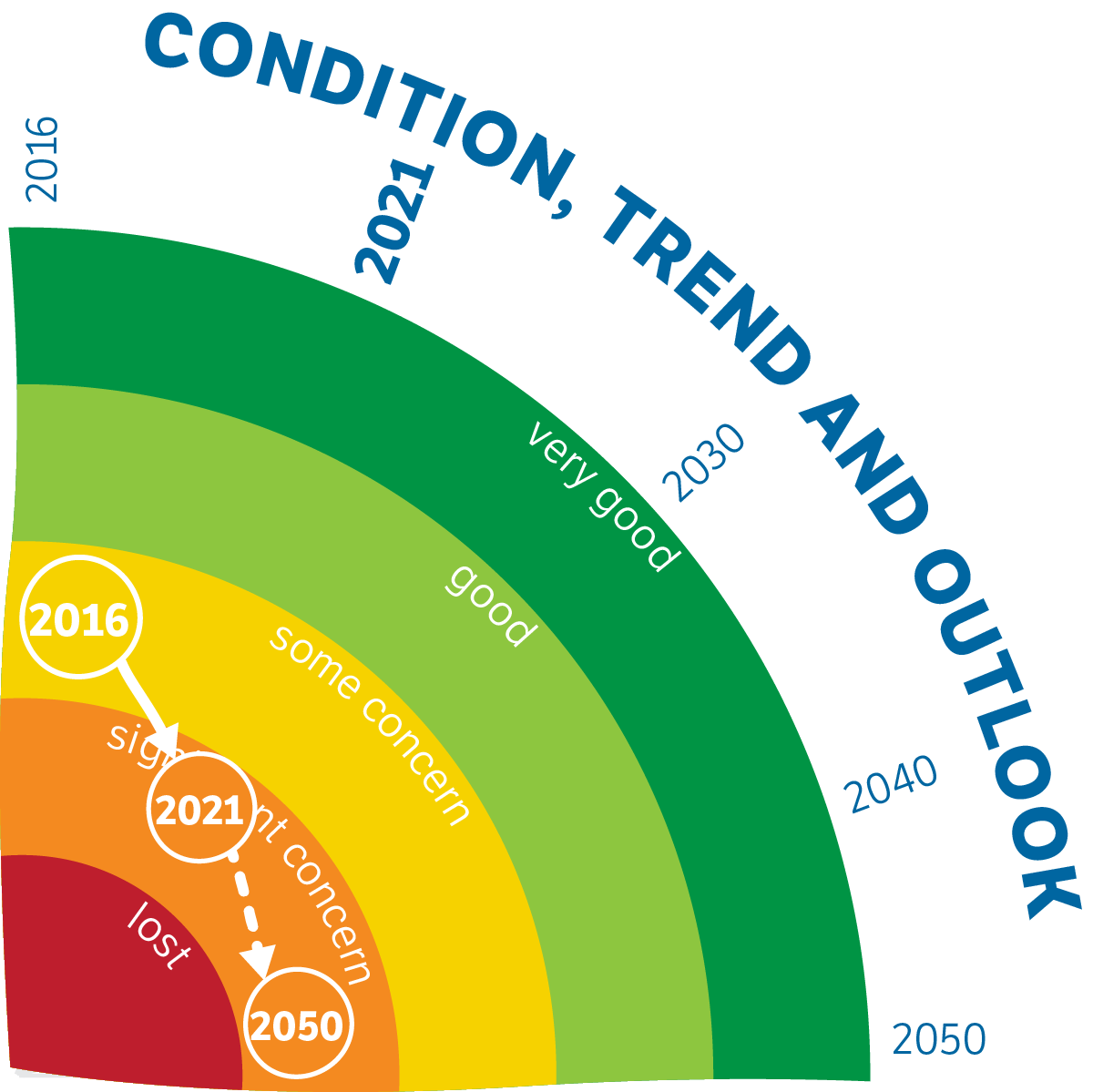

Marine turtles are in decline globally and all six of these migratory species are listed as ‘vulnerable’ or ‘endangered’ under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act). In Torres Strait, their condition has declined from ‘some concern’ in 2016 to ‘significant concern’ in 2021 due to low levels of nesting and hatchling success for green turtles, concerns that very few male hatchlings are being produced, and poor recruitment of juvenile turtles to foraging grounds – leading to similar concerns for other species as well.

Climate change poses the greatest threat with sea-level rise, altered weather patterns and increased sand and water temperatures impacting nesting and hatchling success and feeding grounds. Warmer sand produces a higher proportion of female hatchlings, and there is concern that the number of males in the population is rapidly dwindling, which could lead to catastrophic declines.

Additional information is needed for Traditional Owners to decide how to best reduce threats and produce more male hatchlings. This will build on lessons from the Raine Island Recovery Project undertaken in partnership with the Kemer Kemer Meriam people.

What could happen?

A major decline in the northern Great Barrier Reef (and Torres Strait) population of green turtle is predicted to occur in the next 20-30 years, due mainly to the collapse of hatchling success at Raine Island, where more than 90% of this population nest. A continued decline in turtle populations is expected unless immediate additional actions are taken to mitigate climate change and other impacts. Continued low hatchling success and extreme feminisation will have a catastrophic impact on turtle populations and the future health and well-being of Indigenous culture across the region.

Future actions will need to enhance protection of existing high priority nesting and feeding sites, identify and safeguard potential future sites, protect adult males from traditional take, improve nesting and hatchling success at key rookeries, continue trialling and monitoring of management interventions (such as methods to cool nesting beaches), reduce ghost nets and marine debris, and increase education and awareness of the dramatic decline in the northern Great Barrier Reef green turtle population and required recovery actions.