Key Messages

Torres Strait is a unique and irreplaceable biocultural land and seascape of global significance.

This State of the Environment (SoE) report card recognises Torres Strait is part of an interconnected global ecosystem. The report card links to state, national, and international frameworks, while considering the environment through the cultural lens of local Torres Strait Islanders and Aboriginal people.

This SoE report provides a vital insight into the health of the region and the continuing need for appropriate funding, support and policy commitments to ensure Australia and Queensland meet national and international obligations to protect and restore the outstanding natural and cultural values of Torres Strait.

The key values of Torres Strait are largely intact, but under increasing pressure from multiple threats operating from the international to the local scale. Global, human-induced climate change is the greatest threat to the health of the region’s natural values.

As traditional custodians of the region, the people of Torres Strait rely on the health of their islands and sea country to ensure communities, culture and customary practices remain viable. Country and culture are intricately intertwined – continuing custodianship of land and sea country, and contemporary community- based management approaches, are underpinned by local Ailan Kastom and Aboriginal Lore/Law, incorporating traditional ecological knowledge and governance systems.

Torres Strait Islanders are extremely concerned about the effects of a rapidly changing climate on their homelands, culture, communities, wellbeing and livelihoods. Other drivers of change relate to the eroding of Ailan Kastom, unsustainable resource use within Torres Strait and across the wider adjoining regions, and invasive species.

There are many aspects of the region for which there is little or no recorded scientific information. Future investment will be required to address critical gaps in understanding about the biocultural land and seascapes of Torres Strait for improved environmental outcomes.

The low-lying island communities across the Torres Strait are particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels and may become Australia’s first climate refugees if strong and urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions does not occur.

The first recorded climate-induced mammal extinction event in Australia occurred on a small islet in eastern Torres Strait, and yet the deeper eastern waters of the region may become critical climate refugia for some coral species.

Much good work is underway to protect and manage the unique biocultural values of Torres Strait, but greater investment is necessary to increase capacity to ensure resilience across the region. This will help ensure future management efforts are well targeted, adaptive and enduring.

Introduction

Torres Strait stretches 150km northwards from Cape York Peninsula to Papua New Guinea and up to 300km from east to west. It includes five Traditional Owner nations of Kaiwalagal, Muluilgal, Guda Maluilgal, Kulkalgal and Kemer Meriam (see map 1). The 48,000 km2 region is the most northerly part of Australia and home to about 9,500 mostly Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal People who live on 17 of the region’s 300 islands.

Torres Strait holds a unique place in the natural, cultural, and social fabric of Australia. The region was formed about 10,000 years ago when sea level rose close to its current levels after the end of the last ice age. This flooded the land bridge that existed between Australia and PNG and created a spectacular diversity of natural and cultural land and sea values that are of international significance.

Torres Strait is a pivotal point of connection for Australia. It is the confluence between the large and disparate continental islands of New Guinea and Australia, between the Arafura and Coral Seas, and between the Pacific and Indian Oceans. The largest reef system in the world - the Great Barrier Reef - reaches its northernmost extent here, with the region containing over 1,200 reefs and rich, shallow seagrass meadows. The Coral Triangle, the centre of coral biodiversity globally, sits directly to the north. Torres Strait is Australia’s coral crown and the dugong capital of the world.

Purpose of this Report Card

This report card provides an update on the health of the Torres Strait environment. It draws on available traditional and scientific knowledge and incorporates professional judgement to describe changes in the condition of important natural and cultural values that make Torres Strait such a unique part of Australia.

Since 2006, the TSRA Land and Sea Management Unit (LSMU) has worked with Traditional Owners and Indigenous communities to care for land and sea country. The 2016 Land and Sea Management Strategy for Torres Strait included the first regional state of environment report card ‘snapshot’ based on 16 key land, sea, and people values. These community-identified values are significantly interconnected and galvanised by the continuing practice of Ailan Kastom and Aboriginal Lore/Law.

Torres Strait is comprised of many nations working together as one society to manage their traditional land and sea country, as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have done for millennia. This report card is a foundational element of the contemporary regional approach to collaborative custodianship of country. It operates alongside other plans and programs to support a strategic regional approach to sustainable environmental management in the Torres Strait region, all underpinned by partnerships with Traditional Owners.

This report card has been prepared to help review progress, reflect our current state of understanding, refine priorities, and highlight management actions and investment required to achieve our vision for land and sea management in the region (see opposite). It builds on the 2016 Torres Strait snapshot. It is anticipated that future editions will be improved with a stronger evidence base, and enhanced, co- designed processes for engaging with Traditional Owners and other regional partners.

Outlook and Impacts

Torres Strait is an internationally significant biocultural land and seascape. The region’s key cultural and natural values across land and sea country are intricately intertwined, and the health of most key values is influenced by the health of other key values and the entire, integrated system. Many of the drivers of change that are impacting the region’s natural values are global in scale and are caused by human activities in other parts of Australia and the world. Similarly, the environmental impacts experienced in the region have consequences for human health and wellbeing, as well as the viability and culture of Torres Strait communities. In the face of these drivers and pressures, the outlook for many of the region’s key values is of very significant concern. Management efforts are increasingly focused on co-building human and environmental resilience, including through strengthening regional and local capacity for adaptive management and by enhancing collaborative arrangements with partners.

Unprecedented human-induced changes to our climate system are already impacting key values – and the magnitude of these impacts is expected to increase with continued global warming. Efforts to halt and reverse the effects of climate change at a global level are urgently required to prevent the deterioration of key values. At the local level, sustained partnership efforts are critical to maintain and build the capacity of island communities to understand and effectively address manageable threats to their land and sea country. Strong and enduring support across all scales of Australian and international governance is now urgently required to ensure the key values of this unique region are protected in the face of the challenges ahead.

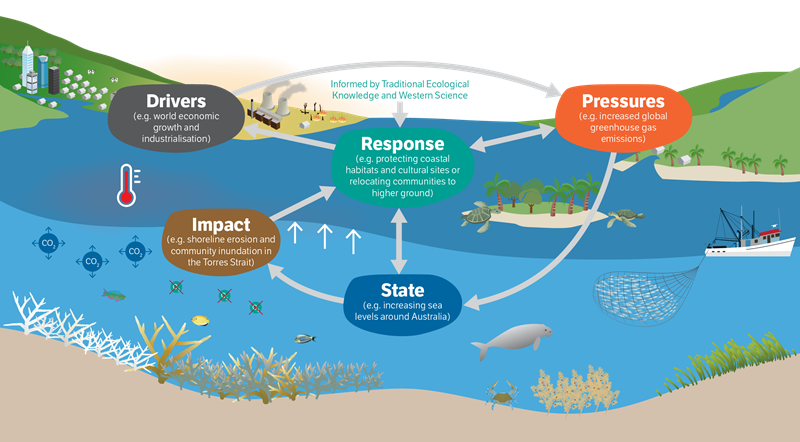

Torres Strait State of Environment process model

Many state of environment reports use a variation of the Driver-Pressure-State- Impact-Response (DPSIR) model to help understand and describe complex environmental and societal interactions and interdependencies at the international to local scale. Under the DPSIR model, driving forces (e.g. world economic growth and industrialisation) cause pressures (e.g. increased global greenhouse gas emissions) that affect the state of environmental conditions (e.g. increasing sea levels around Australia) that lead to impacts (e.g. shoreline erosion and community inundation in the Torres Strait) that require a response (e.g. protecting coastal habitats and cultural sites or relocating communities to higher ground).

This report uses a simplified version of the DPSIR model to assess each of the land, sea, and people key values. Driving forces and the Pressures they cause are collectively referred to as threats. State and Impacts are captured under condition, trend and outlook scores. Potential local management Response options are identified as part of the evaluation of management effectiveness for each key value. Together with the brief narrative the assessments provide a snapshot of what is already happening and what could happen in the future to the Torres Strait environment.

Climate, oceans and atmosphere - key drivers of change

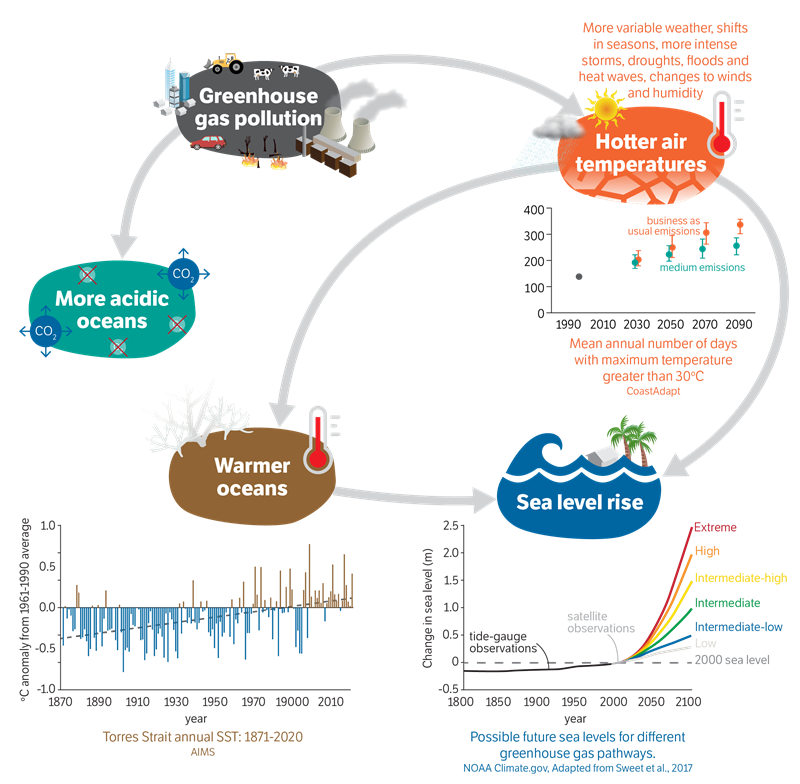

The climate and oceanography of Torres Strait are critical drivers of the culture, biodiversity, and ecology of the region. All aspects of life and ecology are impacted by changes in these critical processes. Human-induced climate change is now driving changes in both oceanography and atmospheric processes that have significant ramifications for the region, its environment, and communities. Whilst average temperature increases in the tropics are lower than those experienced in other regions (like the polar regions), human and ecological systems in the tropics are not pre-adapted to the higher variability that is one of the signatures of a shifting climate. As such, tropical regions like Torres Strait are particularly vulnerable to even small changes in climate.

Over the last century, sea levels in the present-day Torres Strait began to rise again due to human driven increase in greenhouse gases. Sea level rise is not uniform around the world, and in the Torres Strait it has been increasing at about twice the global average rate (estimated to be between 6-8 mm per year in the past decade). Of the 17 inhabited islands, six are particularly exposed to sea level rise due to limited options for retreat away from the coast due to their small size and mostly flat topography. Many communities on other islands throughout the region also occupy low lying coastal areas.

While there is still great uncertainty as to the speed of global sea level rise, the rate and degree to which global emissions are reduced will significantly influence the outcome. According to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, intermediate to high emissions pathways over the coming century will result in between 1-2 metres of sea level rise by 2100. This will have major impacts on all coastal areas and low-lying communities across the region and maps will need to be redrawn. The rate of sea level rise is expected to increase over time and will continue for centuries beyond 2100, even if emissions of greenhouse gases are reduced to net zero by 2050, due to the warming already locked into the climate system. The worst of the impacts can still potentially be reduced through immediate ambitious efforts to reduce atmospheric greenhouse gas levels.

Shifts in seasons are impacting the fruiting and flowering of some plants and the movements of many birds and animals and are likely to further disrupt traditional ecological knowledge of many local systems. Warmer temperatures and greater climate variability will also increase the spread and severity of many pests and diseases and increase fire risk to sensitive ecosystems. Until recently, Torres Strait was home to the endemic Bramble Cay melomys (Melomys rubicola) – the first species known to be declared extinct in Australia due to human caused climate change. Keystone species, including those of great cultural significance to the Torres Strait people, are also under threat. Turtles, coral reefs, and fisheries like the tropical rock lobster fishery are particularly vulnerable to warmer and more acidic ocean environments.

These changes have significant implications for human health and wellbeing as well as for species and ecosystems. While many residents in Torres Strait are used to a tropical climate, warmer temperatures and slight increases in humidity pose a significant health risk through heat stress, particularly for older inhabitants and people with chronic health issues. Data collected so far suggests heat is already a significant risk factor for health.

Warmer temperatures also increase the risk of insect-borne diseases from neighbouring PNG moving into the region. Longer dry seasons are affecting the water security of already water stressed communities. Sea level rise is increasing the frequency and severity of flooding and erosion of low-lying coastal areas, impacting settlements and crops as well as cultural and environmental values. Longer-term sea level rise may force some communities to reluctantly relocate.

Four broad categories of threats have been identified (see www.torresstraitsoe.org.au for detail):

|

Eroding of traditional culture and governance (e.g., passing of Elders, decline in use of traditional languages, loss of livelihoods, poor health and well-being, lack of resources and capacity, migration from the region) |

|

Climate change (e.g., rising sea level, increased sea, sand and air temperatures, ocean acidification, changes to currents, more intense and variable weather, shifting seasons, increased fire risk) |

|

Problematic introduced and native species (e.g., pest weeds, feral animals, Crown-of- Thorns Starfish) |

|

Unsustainable resource use (e.g., habitat alteration, shipping incidents, marine debris, resource extraction, direct use, pollution). |

Threats

While Torres Strait people, sea and land values are still relatively healthy and largely intact, concerted efforts across all levels of government are now vital to protect the region and its communities from a range of ongoing threats operating at the international to local scale.

The key threats affecting the region’s natural and cultural values are identified below. To the extent possible, these threats align with those used in the national SoE reporting framework and the Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report, but we have also identified some unique threats – particularly to Indigenous wellbeing, culture, and livelihoods – for the purposes of this report card. Further background on these threats and how they were used in the key values assessment process is provided online.

The main threats facing Torres Strait’s unique cultural values are related to the passing of Elders, decline in the use of traditional languages, knowledge, governance systems and customs, and associated erosion of culture and traditional governance systems. Unprecedented and escalating changes to climate systems pose the most significant threat to all the region’s values. Declining ocean health, pest plants, animals and diseases, unsustainable coastal development and use of marine resources across the broader region (including in neighbouring jurisdictions) also threaten the region’s biocultural values.

The drivers, or causes of these threats, are primarily global – coming from outside the region. They include population growth, increasing consumption, increasing carbon emissions from fossil fuel use, globalisation of food production systems, media, and homogenisation of cultural values. Local actions can’t stop these threats but can help to reduce or delay their impacts.

The recognised threats are cumulative and interactive – and so are the solutions. This means that mitigation and adaptation actions implemented locally, even to address relatively low-level concerns, can build resilience, and buy the region time while global solutions to overarching risks like climate change and over- consumption are developed.

Moving Forward

This second State of the Environment report card for Torres Strait is a key platform to support improved future management and priority-setting, targeted investment and partnerships for research and monitoring efforts in the region. It complements and works alongside the regional plans, strategies, programs and partnerships in place to support a strategic approach to Torres Strait land and sea management, underpinned by Traditional Ecological Knowledge and community custodianship of country.

Current monitoring programs will be reviewed and assessed in light of this report to help ensure we develop

an increasingly robust dataset and critical indicators to inform management and research priorities and to feed into

the 2026 State of the Environment Report card.

| AIMS | Australian Institute of Marine Science |

| AMSA | Australian Maritime Safety Authority |

| COTS | Crown-of-Thorns Starfish |

| DAWE | Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment |

| DPSIR | Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response FNP First Nations People |

| GBR | Great Barrier Reef |

| ICIP | Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property IPA Indigenous Protected Area |

| IUCN | International Union for the Conservation of Nature LSMU The TSRA Land and Sea Management Unit |

| MEE | Management Effectiveness Evaluation |

| PNG | Papua New Guinea |

| PZJA | Protected Zone Joint Authority |

| RNTBC | Registered Native Title Body Corporate |

| SoE | State of the Environment |

| TEK | Traditional Ecological Knowledge |

| TSRA | Torres Strait Regional Authority |

| UNSDGs | United Nations Sustainable Development Goals |

| WOC | Working on Country |