Narrative

Good water quality is essential to support healthy marine ecosystems and sustainable communities across Torres Strait. Water quality considers pollutants such as oil and plastics, and the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of the water including oxygen content, temperature, and pH.

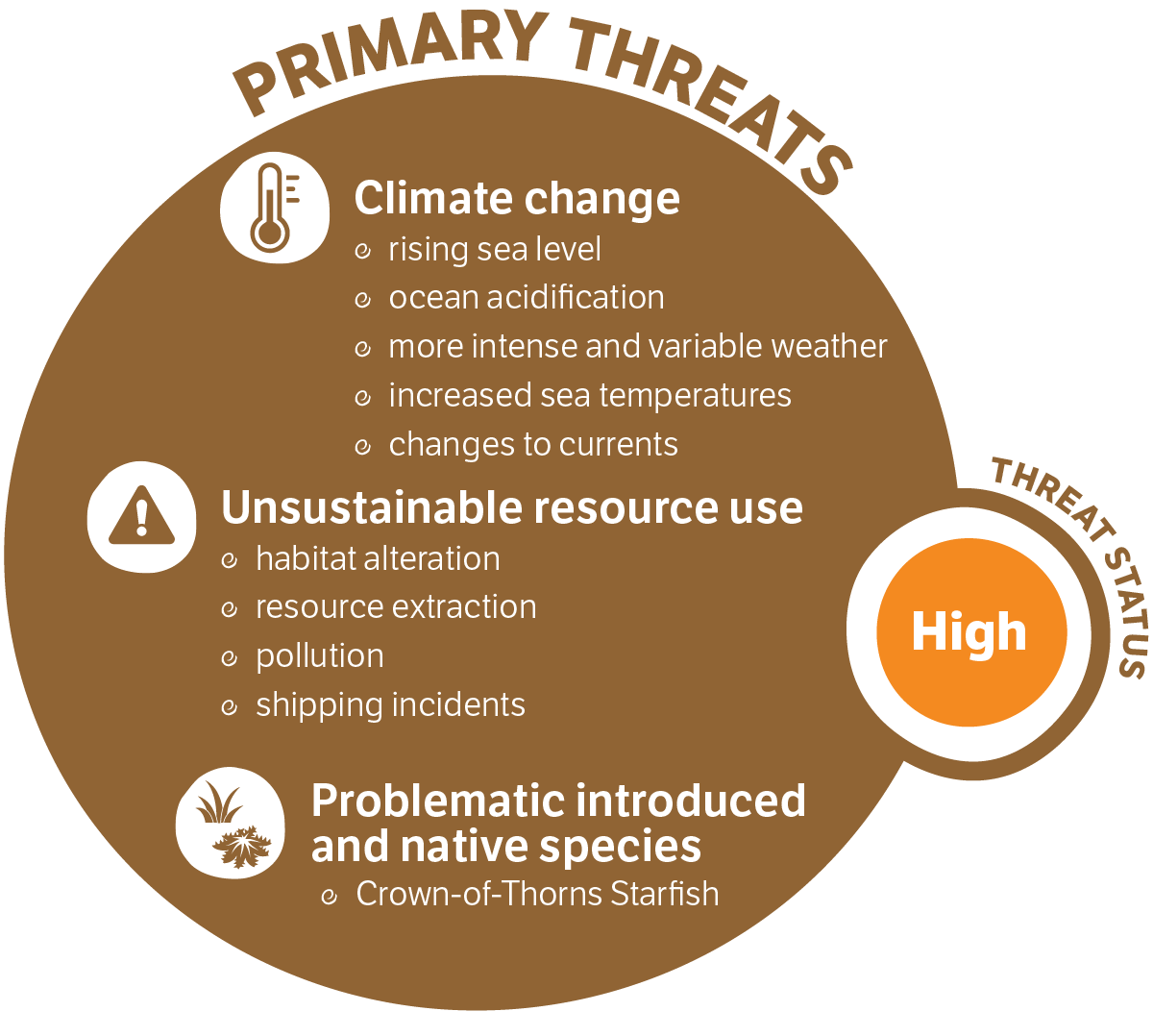

Water quality in the region is influenced by complex oceanography, including strong tidal currents, irregular bathymetry (water depth) offshore upwelling and circulation in the adjacent Coral Sea, northern Great Barrier Reef continental shelf, Gulf of Papua, and Gulf of Carpentaria. The geographic location of the Torres Strait places it at risk from the impacts of shipping, downstream impacts of mining, and land uses in Queensland and PNG.

What is already happening?

Local island waste management practices (including sewage and solid waste disposal) are improving but are still a key source of local marine pollution. Plastic pollution and marine debris (including ghost nets) pose significant concerns to island communities and threaten marine life. TSRA is actively fostering partnerships between communities, rangers and NGOs (e.g. Tangaroa Blue) to collect, analyse, remove and seek to prevent plastic (and other waste) from entering the ocean at its source.

Despite the Torres Strait being declared a Particularly Sensitive Sea Area (PSSA) in 2005, the transit of ships travelling between the Indian and Pacific Oceans through the region remains a significant and increasing threat. While the likelihood of a major shipping incident may be low, the consequences for the region, its ecosystems, people and economy, are potentially extreme. There have been over 20 separate shipping incidents reported since 1970, and over 3,300 transits are made each year through the region. TSRA has driven an effective partnership with the Australian Marine Safety Authority, Marine Safety Queensland, and Local Government to better understand and respond to the social and ecological risks of shipping incidents.

Increasing development, population pressures, resource extraction and more intensive land use practices in the Western Province of PNG are of growing concern. Under certain tidal and weather conditions, plumes of brackish and turbid water from the Fly River (and other local PNG river discharges) may extend into the northeast of Torres Strait. Trace metal concentrations are generally very low in the south and slightly more concentrated towards the north.

What could happen?

Plastics have become the most ubiquitous form of marine debris globally. Micro and other forms of plastics, pose a grave risk to the health of the world’s oceans, including in the relatively clean waters of Torres Strait. Certain species, such as turtles, fish, whales, and birds, face growing risks related to entanglement, habitat degradation and ingestion of plastics.

The region’s limited oil spill response capacity, remoteness, complex currents, and extensive reef networks mean that shipping poses a major and growing threat to the region’s water quality, environmental values, and liveability.

Ocean acidification is likely to become a bigger risk to water quality over coming decades under a business-as-usual greenhouse gas emissions scenario, with adverse impacts on corals and other marine ecosystems within the region. It impairs the ability of marine animals to build and maintain their protective shells and skeletons, which could have major consequences for marine biodiversity and supply of coralline sand for beaches across the region. The impacts of global warming are a more immediate threat with marine heatwaves already causing substantial loss of corals. The warming of the region’s waters also reduces the amount of oxygen the water can carry, posing another risk to the health of marine species.