Narrative

The region’s marine waters, seagrass meadows, coral reefs, mangroves, and wetlands support internationally significant populations of dugongs, turtles and seabirds and productive fisheries. All marine plants, animals, habitats and their interactions, as well as physical, chemical, and ecological processes, are inter-related components of marine ecosystems. A systems thinking approach requires the condition and outlook for all sea values to be considered in the context of overall marine ecosystem health. Although Torres Strait is one of the world’s most intact and interconnected marine ecosystems, it is part of a broader ocean system which is under threat due to global drivers of change.

More than twelve distinct coastal and marine habitats have been identified in the Torres Strait, supporting a rich diversity of species which rely on different habitats during their life history – including many species of cultural significance.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are heavily reliant on the sea for their culture and survival. Human interactions with sea country vary significantly across the larger region, as do the pressures on the marine ecosystem.

The location of Torres Strait at the confluence of multiple adjoining ocean systems is likely to assist the recovery of certain species and habitats following disturbances. However, high connectivity also brings with it the potential for negative impacts from neighbouring areas such as discharges from rivers contaminated by mining pollution and the transport of marine debris and microplastics on ocean currents. It can also result in local disturbances, such as oil spills, having far reaching consequences.

What is already happening?

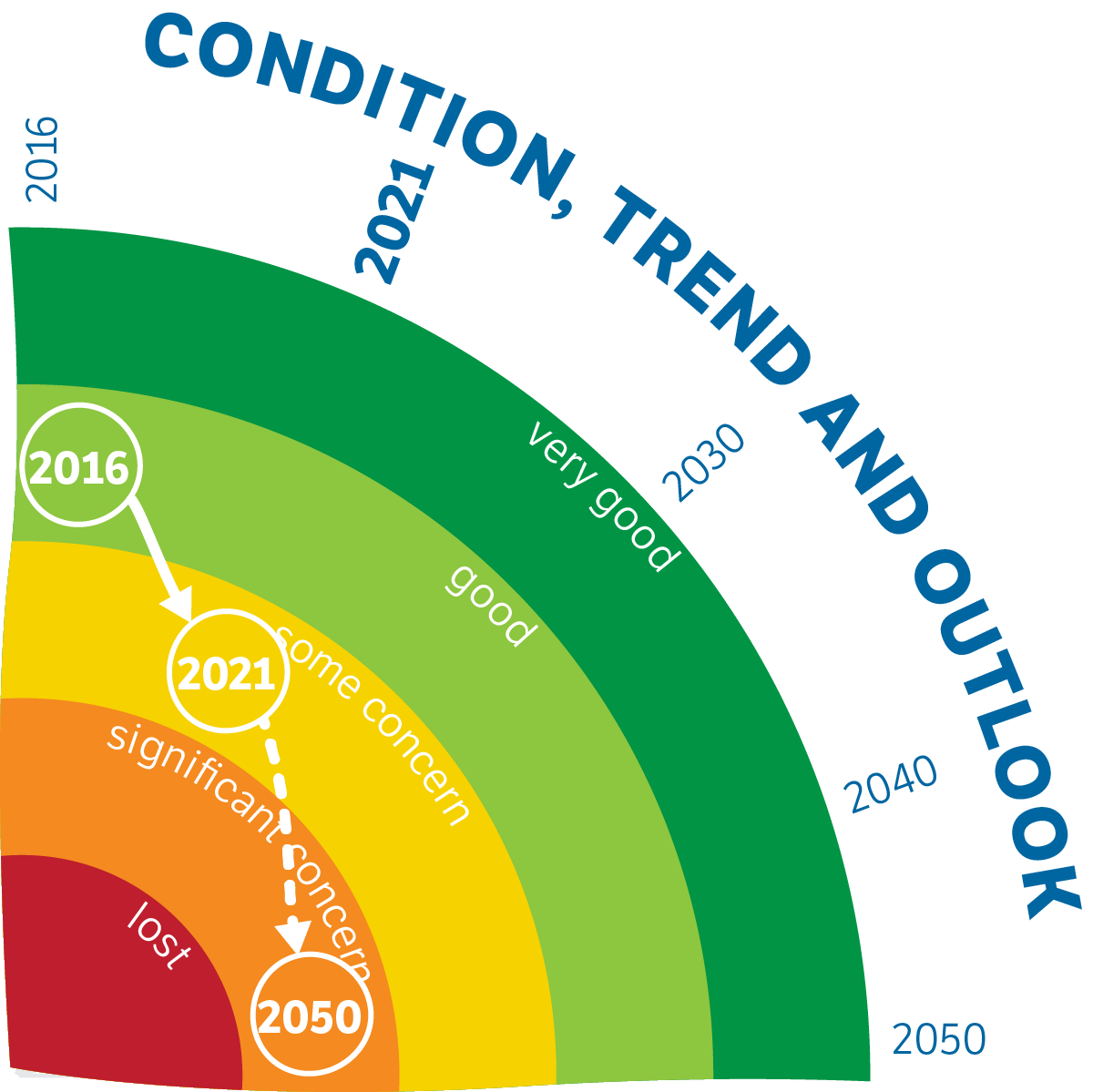

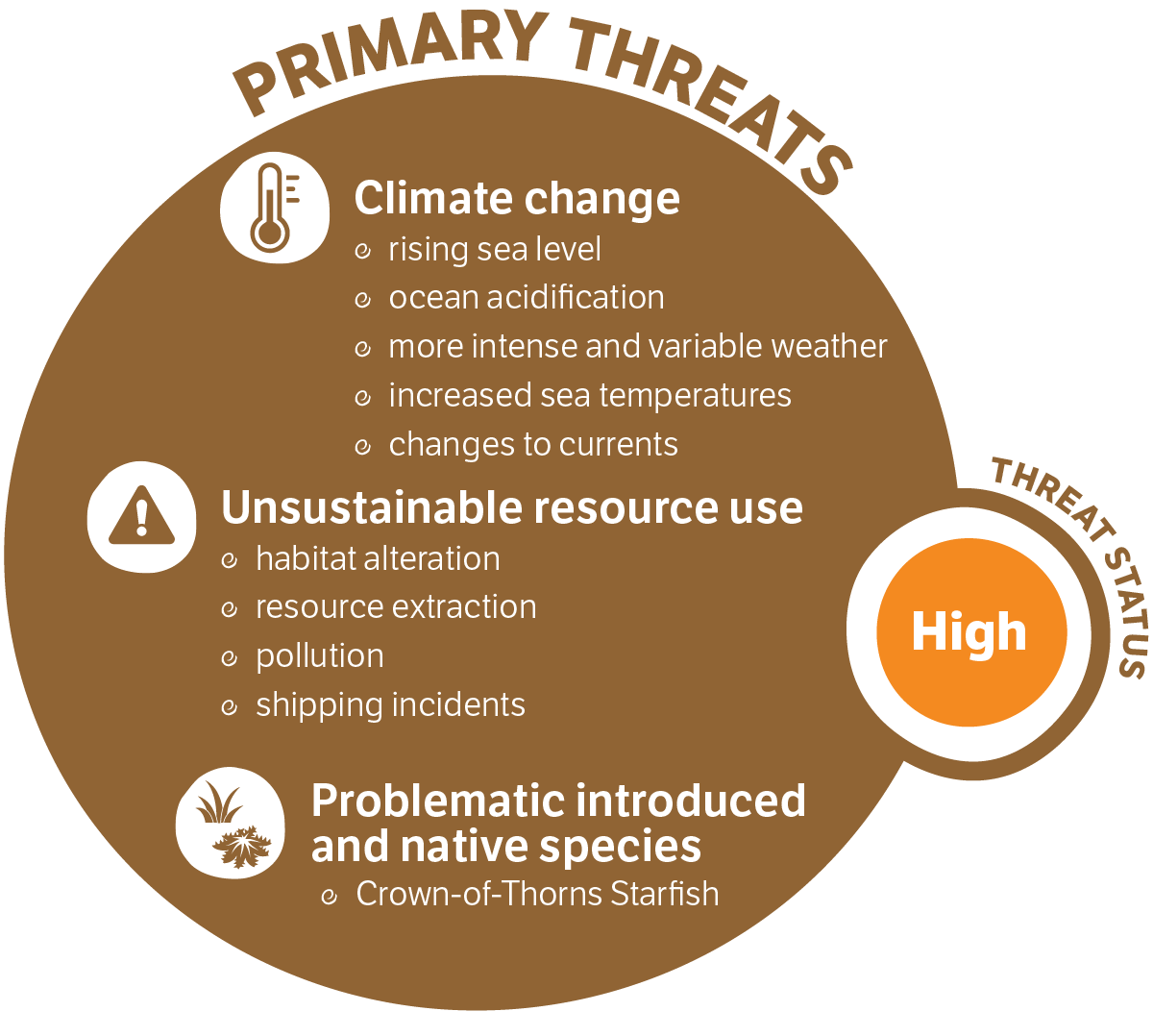

Climate change poses the greatest threat to marine ecosystems and is already impacting many of the physical, chemical, and ecological processes, as well as habitats in and adjacent to Torres Strait. Examples include the widespread bleaching and mortality of corals across central and western Torres Strait in 2016, 2017 and 2020 due to unprecedented marine heatwaves, and erosion and tidal inundation of turtle nesting 4 sites on coral cays in eastern Torres Strait. Rising temperatures have changed the sex ratio of hatching turtles, leading to a critical shortage of male hatchlings.

As climate change makes oceans more acidic it affects the rate at which organisms can deposit calcium carbonate and can alter the survival, growth and abundance of a wide range of organisms including fish, phytoplankton, marine plants, corals and molluscs. Most significantly, these changes are making corals more brittle, susceptible to storm damage and less able to maintain their structural and functional integrity.

Losses in coral cover due to recent mass bleaching events are likely to have impacted the diversity and resilience of these reefs and species that rely on them. Similarly, any continuation of recent seagrass declines in western Torres Strait will likely affect important ecosystem processes.

Crown-of-Thorns Starfish (COTS) have recently been reported at outbreak levels across the eastern cluster of Erub and Mer. COTS can significantly affect ecosystem function, particularly when combined with other impacts on coral reefs such as bleaching.

Major shipping lanes through the region make it vulnerable to the introduction of marine pests and diseases. Diseases affecting marine plants and animals are likely to increase with global warming and further declines in habitats. Species ranges are shifting as they adapt to future climate conditions also has the potential to introduce more pests from areas to the north.

What could happen?

Current climate projections, exacerbated by other local pressures and increasing levels of marine pollution, paint a bleak future for the future health of the world’s oceans. Further ocean acidification, sea level rise, warmer sea surface temperatures and extreme weather events are likely to contribute to an intensification of coral mortality and further population decline. The scale, severity, and frequency at which these impacts are occurring is affecting the ability of marine ecosystems to recover from repeated disturbances and diminishing their resilience.

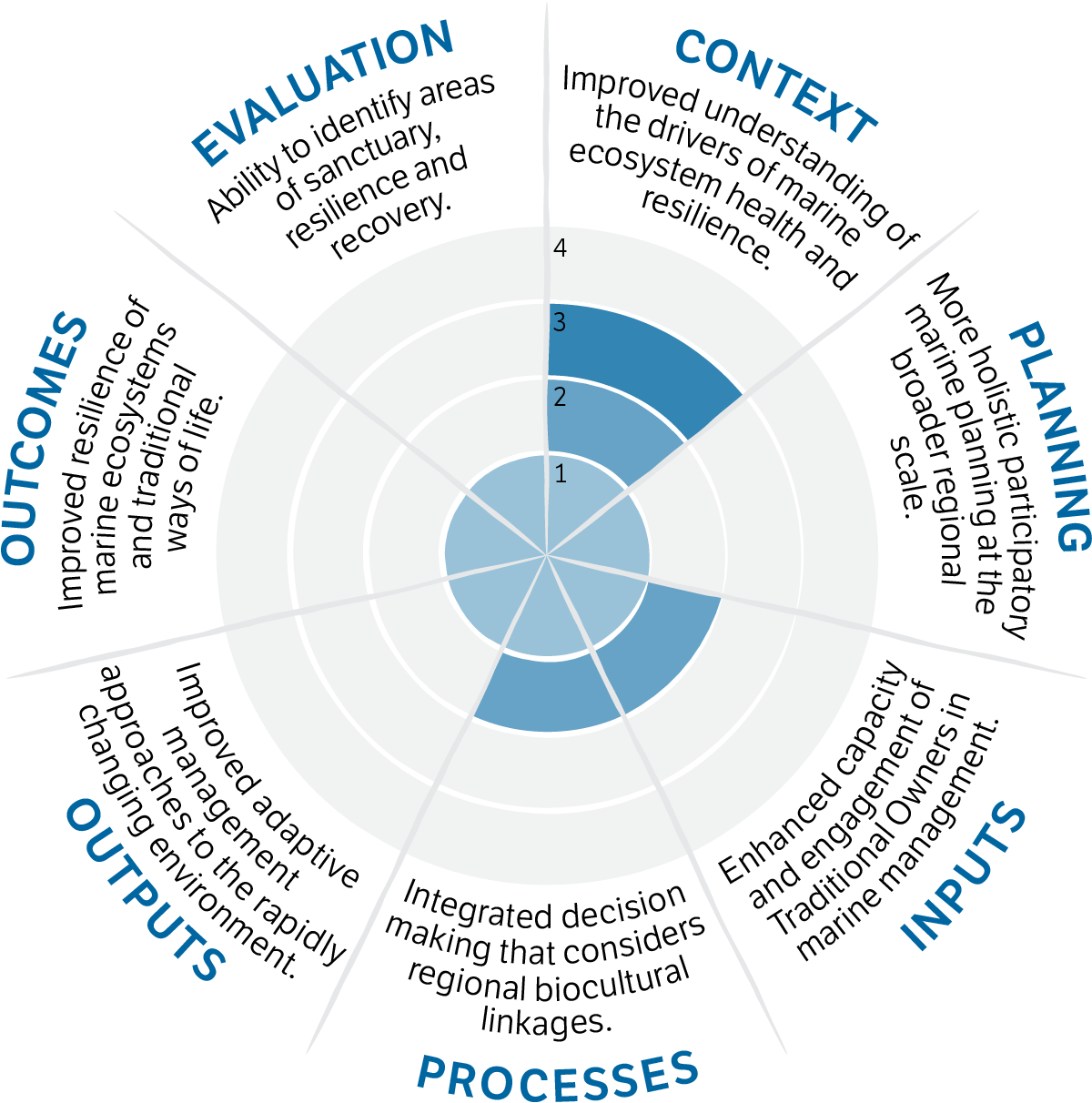

The health of sea country is going to continue to decline due to a changing climate. The future focus will be on strengthening partnerships to accelerate efforts to reduce global greenhouse emissions and influencing practice change at global and regional scales, together with maintaining the health and functionality of local marine ecosystems.

While we have a good understanding of system wide drivers, management needs to be directed towards understanding the local implications of environmental change for communities and the region’s ecological integrity, while reducing pressures where we can and building resilience in priority species and ecosystems.